Question of the Month w/ Ted Brewer: 50 Years of Cruising Sailboat Evolution

"The trunk cabin is “streamlined” akin to a Buck Rogers rocket ship but, to me, such radical streamlining seems to be somewhat unnecessary on a vehicle that will rarely travel faster than a man can run."

-Ted Brewer (see below)

As you may recall, I started a series of guest blog posts late last year featuring some of my favorite sailboat designers, including Ted Brewer and Bob Perry. This particular post is a continuation of my "Question of the Month with Ted Brewer" series. This month, I asked Ted, "Do full keel boats and classic designs still make sense for cruisers today, or have these boats run their course?". Ted's response below is an excellent historical perspective on cruising (and racing) sailboat evolution over the past 50 years. Whether you're a fan of classic designs featuring full keels, skeg rudders, and heavy displacement like myself, or you favor today's modern thin fin keels, ultra-short overhangs, and light displacement, I think you'll enjoy Ted's thoughts.

As always, BIG thanks to Ted for taking the time to graciously contribute to my blog! If you're interested in reading his previous guest blog posts for SailFarLiveFree, please visit the Sailboat Reviews page.

50 Years of Cruising Sailboat Evolution by Ted Brewer

I thought it would be interesting to look back over the changes in boat design that have come along in the 50 plus years since May ’57, when I was discharged from the army. That’s when I got into the boating business, beginning as a yacht broker at George Cuthbertson’s Canadian Northern Company, later to become famous as C&C Yachts. The firm was located on the outskirts of Toronto , Ontario Lake Ontario

My father was Canadian navy so I learned to sail on 27 foot navy whalers and 14 foot dinghies when I was a teenager, but I knew literally nothing about the sailing yachts of the late 1950s, and I was keen to learn. Thanks to George, and his partner Peter Davidson, I found a berth aboard Vision, a 48 foot eight metre class sloop, sailing out of Toronto Toronto

At the time, George Cuthbertson, was designing a new 54 foot keel/centerboard ocean racing yawl and construction had already started at Cliff Richardson’s yard in Meaford , Ontario

|

| Brewer-designed 42' alumninum s/v Sandingo has cruised the S. Pacific extensively |

Of course, there were plenty of CCA type deep keel yachts sailing and racing as well, many of them built in the ‘30s, and many newer ones designed and built post war from the boards of Olin Stephens, Bill Luders, Phil Rhodes, Ray Hunt, John Alden, Laurent Giles and other talented designers both in North America and abroad. It must be noted that fiberglass construction was in its infancy in the late ‘50s so virtually all of these boats were custom built, usually of wood, and were primarily designed as cruising yachts with racing potential as a plus, but only if they were successful at bringing home the silver. Even the smaller yachts were custom built as there were no large production facilities turning out great numbers of boats and, for that matter, no demand for great numbers of boats either. Luders was building the 26’ L-16s of hot molded wood construction but their production was very small by modern standards.

The 25’ Folkboats which we imported, used, from Denmark Scandinavia but each shapely lapstrake hull was individually built to order in small boatyards. They were lovely little craft and I certainly envied their lucky owners. The boats cost about $2,500 delivered to Toronto

The cabin featured only two settee berths with an exposed toilet, or a bucket, up forward. A few of the boats had two child’s berths in the forepeak, but they were the exception as you can only put so much into 19 feet of waterline. The cockpit was deep and comfortable, but not self bailing and that, in itself, would frighten off many of today’s sailors. Yet the Folkboats raced in all weathers, won their share of heavy weather events, and sailed all over the Great Lakes and coastal waters with their happy crews. Indeed, several modified Folkboats sailed and raced across the Atlantic.

Larger yachts were not much better off in their accommodations though. It was generally considered that no boat under 30 foot LOA could have standing headroom. Even 30 to 40 footers, and larger, lacked pressure water systems and the galley sinks were supplied by hand pump. There was no hot water heater, no electric refrigeration and little decent lighting as you could only do so much with the puny 6 volt batteries that were the standard in those days. Indeed, kerosene navigation and anchor lights were quite common; otherwise, you could run down the weak little car battery overnight and awake to find that you owned a true 100% sailboat.

|

| Brewer-designed Pacific 42 belonging to Burl Ives |

Fortunately, the gasoline engines of that era were low compression types and many small engines had the luxury of a hand crank to start them when the battery died, as it so often did. Diesel engines were unheard of except in larger yachts and, even then, of low power by today’s standards. As I recall, the heavy displacement 54’Inishfree had only a four cylinder Mercedes diesel of about 40 horsepower. She managed quite well with it, but many owners of 40 footers would consider that to be inadequate power today.

The necessity for custom building in wood kept the price of a new yacht on the high side and the numbers built relatively small. Yachting definitely was a gentleman’s sport, a wealthy gentleman’s sport by today’s standards. Then, in the late ‘50s, things began to change with the introduction of fiberglass reinforced plastic (FRP) construction. The US Navy experimented quite successfully with FRP personnel boats in the late ‘40s but the first large FRP yachts were not produced until 1956 when Fred Coleman introduced the handsome Phil Rhodes designed Bounty II, a keel sloop.

|

| Brewer-designed Puffin 38 (s/v Tusaire) features twin fin keels and a central ballast pod. She's cruised a lot of bluewater, from Seattle to the Bahamas and back |

The Carl Alberg designed 22’6” Sea Sprite, introduced in ’58, was primarily a daysailer with weekend aspirations. The big surprise at the 1959 New York Boat Show was another Alberg design, the first true production small cruising yacht, the Pearson Triton. With her standing headroom and an introductory price of $9,700 the little Triton was such a success that Pearson built 750 of them before production stopped in ’66. With the Triton’s success, Carl Alberg became one of the major cruising yacht designers of the 1960s by specializing in full keel sloops with typically long ends, narrow beam, good draft, husky displacement, a high ballast ratio and a flattish sheer line. Alberg designs were popular and built by Pearson, Whitby Cape Dory Whitby

In 1963 the beginning of the end came for the CCA full keel and keel/c.b cruiser-racers when the first of the Bill Lapworth designed Cal 40s was built by Jensen Marine in California

For the next few years there was considerable discussion about the merits of fin hull designs and many designers stuck to full keel types, particularly for cruising yachts. Indeed, my first production design after leaving Luders in ’67 was a full keel cruiser, the Douglas 31, a standard CCA type hull with the long ends and other general features of that rating rule. Other designers were experimenting with fin hulls, particularly if the boats were cruiser/racers, and the fins grew increasing smaller fore and aft as time passed. Practical Sailor summed it up by noting that the Cal 40’s fin was small compared to a full keel hull of her day but, when compared to a contemporary fin, it hardly justified the name. Such is progress.

In lateral shape, the designers experimented with rakishly raked fins and fins that looked as they had been modeled after a shark’s. They certainly appeared to be fast but, over the years the fin leading edge has become less raked and the trailing edge almost vertical. Still, many boats were very CCA’ish in the late ‘60s with long ends, short waterlines and husky displacement, even if they did sport a fin. Despite the Cal 40’s success, it appeared that few designers took Lapworth’s other innovations seriously as long as they were racing under the CCA rule or, across the pond, under the Royal Ocean Racing Club Rule.

This began to change in 1969 when the International Offshore Rule was developed. This rule measured displacement not, as the CCA had, by designer’s certification or, later, by actually weighing the boat but by measurements taken from the hull. Naturally, it did not take designers very many years to figure out how to beat the rule with distorted bulges and even chines in the hull to increase the “displacement” factor. As well, ends became very pinched to exploit the rule and the boats came out with V shaped transoms and diamond shaped deck plans. The rule eventually produced unseaworthy yachts in the quest for a low rating and this resulted in many boats being abandoned and lost, and 15 sailors killed, in the ’79 Fastnet Race due to an unusual freak storm.

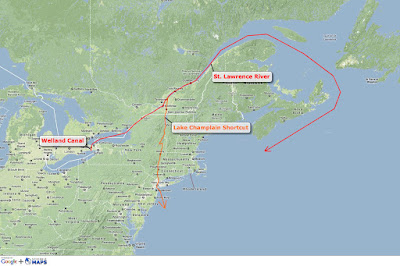

Even before this tragedy, cruising yachtsmen had grown away from the extreme IOR boats and many fine, seaworthy fin keel and full keel yachts were developed to meet a demand for a sensible, good performing and seaworthy auxiliary cruiser. In any case, I was never keen on the IOR rule and was not interested in producing such freak boats. My own favorite design is a custom one-off cruiser, Black Velvet II, a 43 foot fin hull, skegrudder cutter with a 35’4” waterline and a D/L ratio of 251 that I designed in ‘71 [You can read more about Ted's BV II here]. BV II, as I call her, was later put into production in Hong Kong as the Cape North 43 and the latter won a few notable ocean races. Still, the true raison d’etre for the design was to provide BV II’s Montreal Lake Champlain , yet a boat capable of voyages to Bermuda , the Caribbean or even trans_Atlantic when time permitted.

|

| Brewer-designed Carib ketch, built by Cape North |

Many other designers also created fine non-IOR cruising yachts, both full keel and fin keel but, in ‘74, Bob Perry’s Valiant 40 fired the cruising sailor’s imagination. The Valiant is also a fin hull, skeg rudder cutter, 39’11” overall on 34’ waterline with a D/L ratio of 256. Her double ended hull with a full deck line and a Scandinavian shaped stern was apparently based on the marketing success of the very, very full keel Westsail 32. Perry felt that a truly good performing double ender would attract sailors, and he was right. The Valiant 40 was a success from the start but, when one sailed By Francis Stokes in the 1980 OSTAR, won its class and was the first American monohull to finish, the boat became legend.

By this time the serious ocean racing sailor and the cruising/racing sailor were parting ways. The IOR rule gave way to the International Measurement System but there have been problems with this also. The RORC finally came out with their rule and it was approved for international competition in ’04. Now different areas of the world sail under different rules and racing appears to be very fragmented indeed. I have not followed handicap rule development in the last few years as it simply does not interest me any more. When racing yachts started to sport advertising (Smoke Wheezies, You’ll Die Laughing) and were sailed by highly paid professional crews I simply quit paying ocean racing any attention whatsoever.

Of course, there have always been thousands of true amateur sailors, and always will be, who enjoy taking part in club racing and overnight events in boats that are fast cruisers, or vintage racers, but are not necessarily the ultimate in new rule beating racing design and equipment. Fortunately for these folks, the popular Performance Handicap Racing Rule allows them to compete fairly with a wide variety of boats.

There are also many sailors who never race and who swear by the steadiness of full keel designs such as Bruce Bingham’s little Flicka, Lyle Hess’s Nor’sea designs, the chunky and able Island Packets, the very husky Hans Christians, and similar craft of even older vintage. However, the mainstream design of cruising yachts has changed significantly over the years as owners demand more accommodations, greater amenities and improved performance. Fin hulls with spade or skeg rudders are widely accepted for both inshore and blue water cruising while the boats have grown in waterline and beam and, at the same time, dieting and losing avoirdupois. The great majority of designers and builders turn out able, good performing cruisers but some contemporary yachts are so beamy and of such light displacement that I would hesitate to take them very far offshore regardless of their size, and that includes craft as large as 60 feet!

|

| Ted Brewer's very first production boat design - a Douglas 31 from 1967. Notice the short waterline & long overhangs from the CCA rule. |

As well, imports from Europe in the last two decades have given many newer sailors a very different idea of what a boat should look like compared to the yachts of even 30 years ago. Today, to many sailors, Euro design in boats is all the rage, featuring a flat sheer, high freeboard, reverse transom (preferably with “sugar scoop”), super wide stern, super light displacement and a deep, narrow fin. The trunk cabin is “streamlined” akin to a Buck Rogers rocket ship but, to me, such radical streamlining seems to be somewhat unnecessary on a vehicle that will rarely travel faster than a man can run.

Such boats would have L. Francis Herreshoff rolling in his grave and, frankly, they do nothing for me either. That is to be expected after the years I’ve spent admiring and studying the work of so many of the truly great yacht designers both in North America andEurope . Indeed, I still long for the days of the old CCA rule and the handsome and able yachts that were produced; a little short on accommodations and all mod cons, perhaps, but long on beauty and seakindliness.

Fortunately there are designers alive today, men like Mark Ellis, German Frers, Rod Johnstone, Chuck Paine, Bob Perry, and others who can still draw a sweet sheer line, balanced ends and a generally handsome, good performing, cruising yacht design, whether it is of traditional or contemporary styling, or of wood, fiberglass or metal construction. Fortunately too, there are still owners who appreciate such fine, well thought out and beautiful yachts, and the craftsmen who can build them.

For more perspective from Ted Brewer, check out his book: Understanding Boat Design:

For more perspective from Ted Brewer, check out his book: Understanding Boat Design:

So does that mean it's OK to sail a Laser - or not?

ReplyDeleteOf course! I learned the very basics of sailing aboard a Laser using the trial and (mostly) error method. It's exhilarating to be that close to the water getting sprayed and feeling such a close connection to the boat.

DeleteKeep on working, great job!

ReplyDelete