Remembering a November Gale - 100 Years Later

“No lake master can recall in all his experience a storm of such unprecedented violence with such rapid changes in the direction of the wind and waves and its gusts of such fearful speed! Storms ordinarily of that velocity do not last over four or five hours, but this storm raged for sixteen hours continuously at an average velocity of sixty miles per hour, with frequent spurts of seventy and over.” (From the Lake Carriers Association Report of 1914)

I’ve always been interested in Great Lakes shipwrecks and am a sucker for nautical lore, so it’s no surprise that I’m inspired to write about such things at least a couple of times per year here at SailFarLiveFree.com. [See the end of this post to find my previous shipwreck ramblings]. This week happens to mark the 100th anniversary of an event that added many chapters to the maritime history of the Great Lakes, which is an even more fitting reason for this particular post.

Imagine 35-foot waves, whiteout blizzard conditions, hurricane force winds (some reaching 90 mph) and the loss of 250 lives and 12 ships from a storm lasting 4 days. If you were alive 100 years ago this week (from November 7 – 10 of 1913) in the Great Lakes region, you could have witnessed this furious storm that makes the term “Gales of November” so ominous.

|

| The headlines from the Nov. 13, 1913 Detroit News |

The Great Lakes storm of November 1913 started with a seemingly common fall weather pattern as a weak low pressure system tracked east across the southern United States from November 6-8, 1913. The root of the storm’s ferocity came from a second low pressure system carrying unseasonably cold Arctic air out of Canada and into the Upper Great Lakes beginning on the morning of November 7. By the morning of November 9, the southern system engulfed the northern system and grew into what is now regionally known as the “White Hurricane”.

Hurricane force winds (>74 mph according to the Beaufort scale) were only part of the story. The “White Hurricane” was labeled as such because of the widespread and heavy snow that accompanied it. Lake effect snow was whipped by the wind into squalls that blinded ships and drifts that crippled cities such as Port Huron in Michigan and Cleveland in Ohio. Cleveland recorded 17.4 inches of snow in a 24-hour period and a three day total of 22.2 inches, setting the city’s 24-hour record.

The real toll of the storm was felt by mariners and paid to the Great Lakes themselves. A total of 12 ships were sunk and lost completely while at least 31 others were driven ashore by wind and waves. Worst of all, 250 lives were lost on the lakes during the 4-day storm of 1913. The following is a summary I put together of the losses. Note – While I’ve tried to capture only factual information, in some cases my research revealed many conflicting details about the number of crew, ship lengths and the whereabouts of the shipwrecks.

|

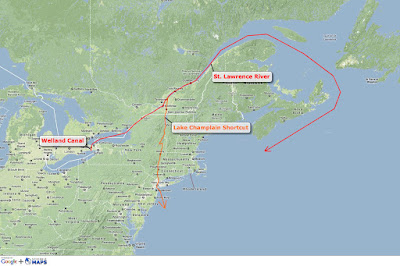

| A map showing the location of the ships that were lost during the storm of 1913 (Click the image for a larger view) |

Leafield: A 269-foot steel freighter loaded with steel railroad rails that was lost near Thunder Cape in Lake Superior with Captain Charles Baker and 17 crew aboard. Leafield initially grounded on Angus Island before being pushed free by the large waves only to sink farther offshore.

Henry B. Smith: A 525-foot steel freighter loaded with iron ore that left port on November 9 from Marquette, Michigan at the height of the storm never to return. Captain James L. Owen and 25 crew were aboard when she went down. The wreck was located in 535 feet of water off of Marquette in May of 2013. [Check out the underwater video footage of the wreck here]

Plymouth: A 225-foot former steamer converted to a 213-foot long 3-mast schooner barge used for hauling lumber. She was being towed in Lake Michigan by the tug James H. Martin when the tug had difficulty with the storm conditions and reportedly became disabled. The Plymouth and crew were left at anchor in the lee of St. Martins Island at the mouth Green Bay to wait out the storm. When the tug returned to retrieve the Plymouth and her 7 crew members, the schooner was not there, lost to Lake Michigan. Wreckage from the Plymouth was found in 1984 near Poverty Island.

Plymouth: A 225-foot former steamer converted to a 213-foot long 3-mast schooner barge used for hauling lumber. She was being towed in Lake Michigan by the tug James H. Martin when the tug had difficulty with the storm conditions and reportedly became disabled. The Plymouth and crew were left at anchor in the lee of St. Martins Island at the mouth Green Bay to wait out the storm. When the tug returned to retrieve the Plymouth and her 7 crew members, the schooner was not there, lost to Lake Michigan. Wreckage from the Plymouth was found in 1984 near Poverty Island.

Argus: A 436-foot steel bulk freighter that went down while headed north in Lake Huron about 13 miles north of Point Aux Barques. All crew members (different sources claim from between 24 to 28 crew) were lost. The wreck of the Argus was discovered upside down on the bottom of Lake Huron at a depth of 250 feet in 1972.

James Carruthers: A 550-foot steel bulk freighter that was carrying 375,000 bushels of wheat from Fort William, Ontario in Lake Superior to Midland, Ontario in Lake Huron. At the time, she was Canada’s newest and largest freighter. She refueled in DeTour on November 9 and went down shortly thereafter in Lake Huron with Captain William H. Wright and a full crew of 21 on board. The James Carruthers wreck remains missing today, though several bodies from crew members and Captain Wright washed up on Lake Huron’s shores in the week after the storm.

Hyrdus: A 436-foot sister ship to the Argus (see above) that was carrying a load of iron ore not far behind the Carruthers (above). The Hyrdrus was heading southbound shortly after entering Lake Huron when she was overcome by the massive storm and sank with Captain John H. Lower and 27 total crew on board. The Hyrdus is still missing as of 2013.

John A. McGean: A 432-foot steel freighter loaded with coal out of Lake Erie and bound for Lake Superior when she reportedly broke in pieces and quickly sank just north of Michigan’s thumb in Lake Huron. The wreck was located in 1985 in 175 feet of water. Her captain and 23 crew were lost.

Charles S. Price: A 504-foot steel bulk freighter hauling coal northbound in Lake Huron. While no one knows for certain what happened during her final hours, speculation existed that she collided with Regina (see below) or at least had some encounter as bodies were reportedly found from both vessels wearing the other ship’s life jackets. The Price was seen floating belly up for several days after the storm, but eventually sank and now rests in 72 feet of water off Lexington, Michigan. Divers have confirmed that the Price shows no signs of collision with another ship.

|

| The Charles S. Price floating upside down on the surface after the storm |

Regina: A 269-foot steel freighter that was headed north in Lake Huron, but was forced by wind and waves to retreat south until she hit a shoal and anchored in distress. The ship sank within half an hour, taking the life of Captain Edward H. McConkey and all 19 crew members. After the storm, at least 10 bodies were found on the beach near Lexington and another 2 were discovered with a capsized lifeboat still in Lake Huron.

Isaac M. Scott: A 504-foot steel bulk freighter that was last seen during the morning of November 9 south of Thunder Bay carrying a load of coal bound for Milwaukee. All 28 lives on board were lost without a trace, except for a single lifeboat that was found near South Hampton, Ontario. Today the wreck of the Scott is lies quietly inverted on the bottom off Thunder Bay Island. Her final resting place was discovered in 1976.

Wexford: A 250-foot steel freighter that carried 96,000 bushels of wheat along with her captain and 20 crewmen to her grave when she went down in the storm. The shipwreck of the Wexford was discovered in 75 feet of water in 2000.

|

| Some of the Wexford's crew were found on the shore near Goderich, Ontario |

Light Vessel 82: A 95-foot steel lightship (a ship that acts as a lighthouse) built in my homeport of Muskegon, Michigan. This particular lightship was tasked with marking the approach to busy Buffalo Harbor in Lake Erie when she went missing during the storm of 1913 along with her captain and crew of 5. LV 82 was found on the bottom in 62 feet of water and salvaged the following spring. LV 82 was the only ship lost on Lake Erie during this storm.

Improved weather forecasting and modern freighters have made tragedies like the aftermath of the 1913 storm far rarer than they use to be, but it still takes a special mariner to ply the seas when the beaches are empty and the pleasure craft are hibernating. The above accounts are a somber reminder of why I be content with my own little ship safely hauled for the Gales of November.

Hungry for more lore? Try some of my previous shipwreck posts:

Interested in seeing Great Lakes’ storms in action? I’ve got you covered there too with these videos/photos I’ve taken over the last several years:

Comments

Post a Comment